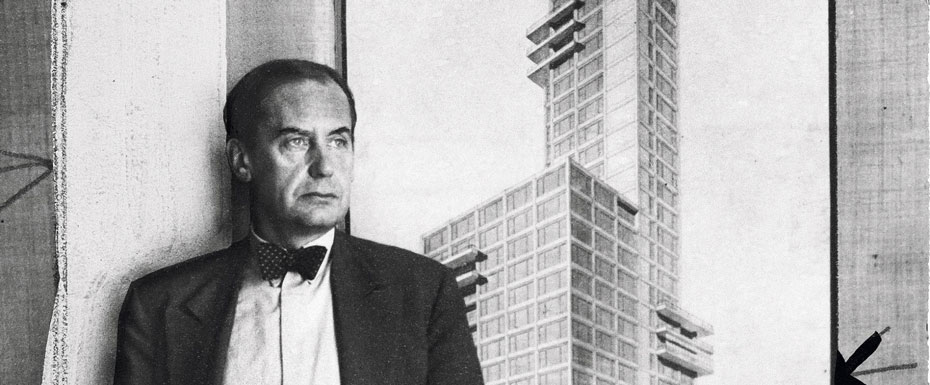

Walter Gropius was a key figure in the architecture of the 20th century, the theorist of modernism, the founder and main ideologist of the revolutionary German school. Restrained and cold-blooded, he stood out from the circles of his eccentric colleagues and extravagant Bauhaus students. The originality of the great architect was expressed primarily in his work. He had an excellent ability to find and nurture talents. It is impossible to overestimate the historical and social significance of his projects in Europe and the United States that had appeared over the 50 years of his creative activity.

Childhood and Adolescence

Walter Gropius was born on May 18, 1883, in Berlin. The choice of his future profession was largely predetermined by his closest circle – his father was engaged in state-building, and his great-uncle was an architect.

At the age of 20, Walter entered the Technical University of Munich, where he studied the history of architecture, design, and engineering. After spending a little over a year in Munich, due to the illness of his younger brother, Gropius returned to Berlin, where he continued his studies at the Berlin Higher Technical School.

Career Start

Walter traveled around Spain for a whole year, taking inspiration from the local architecture. Upon his return to Berlin, the architect got a job in the architectural studio of Peter Behrens, the founder of German industrial design. While working on industrial projects, he was introduced to modern construction methods and the use of the most advanced materials.

In 1910, Gropius, in partnership with Adolf Meyer, founded his own firm in Berlin. At the same time, he joined the German Werkbund – an alliance of architects and designers who advocated the industrial mass production of art objects. At first, due to the lack of large orders, the architects designed furniture, wallpapers, and vehicles.

The first major project was the construction of factory buildings for the Fagus plant. A year later, Gropius and Mayer participated in the Werkbund exhibition in Cologne, where they presented the Model Factory – an administrative and production building with glass staircase cylinder towers. The innovative concept was a resounding success.

In 1914, Walter Gropius’ rapid architectural career was abruptly interrupted by the First World War: he fought for four years on the Western Front, was seriously wounded, and narrowly escaped death.

Bauhaus

The war greatly influenced the theoretical views of the architect. Walter Gropius returned to Germany with an awareness of the need for radical changes and a firm intention to set new boundaries in architecture.

In 1918, Gropius became the director of the combined Saxon-Weimar Higher School of Fine and Applied Arts, which he soon renamed as Bauhaus. The experimental approach of the school, incorporating the features of neoplasticism and Soviet constructivism, was outlined in his Manifesto (1919). The mid-1920s marked a turning point for the Bauhaus as Gropius embarked on a course towards functional, accessible design and industrial production ‘adapted to the modern world of radios and high-speed cars’.

When the right-wing political forces rose to power, the Bauhaus became subject to criticism, and the school eventually lost state funding. In March 1925, the Bauhaus closed its doors in Weimar and moved to the small industrial city of Dessau. In 1928, having lost the favor of the Weimar authorities and school colleagues, Gropius left the Bauhaus and went to Berlin with the goal of fully devoting himself to private projects.

Mass Construction

In his quest to tackle the shortage of affordable social housing in the post-war period, Walter Gropius worked on large housing projects. Later, Gropius criticized the correct geometric facades and typical layouts characteristic of the works of that period, calling them ‘the curse of uniformity’.

In his quest to tackle the shortage of affordable social housing in the post-war period, Walter Gropius worked on large housing projects. Later, Gropius criticized the correct geometric facades and typical layouts characteristic of the works of that period, calling them ‘the curse of uniformity’.

The architect was experimenting with precast concrete structures. In the village of Dessau-Törten, according to his project, 370 residential buildings of the same type were erected in three stages. He was the one to develop the method of line building of residential areas, which implies the same orientation of all buildings. Using this method, Gropius designed the village of Dammerstock and the Siemensstadt residential area on the outskirts of Berlin. Subsequently, the developments of the German modernist had a significant impact on social construction in Germany and Eastern Europe.

America

After the victory of Hitler’s government, the position of Walter Gropius became precarious. He never was and could not be a Nazi: it was not in his nature to worship, and the anti-Semitic policy of the authorities terrified him. In search of at least some kind of work, the architect entered the Imperial Chamber of Culture. This desperate step did not have the desired effect: in the winter of 1933, his financial standing became so dire that he sold his beloved convertible and rented out most of the apartment.

Deeply devoted to his country, Gropius did not want to leave Germany, but his liberal views and compromising connections gave him no choice. In 1934, the architect and his family fled secretly to Great Britain under the pretext of going to a conference. In London, the architect worked for the Isokon modernist bureau.

Fearing a German occupation, Gropius accepted an invitation from Harvard University, emigrated to America in 1937, and took over as professor of architecture. Soon after the move, he took up the design of his own home in the suburbs of Lincoln. The building, which became the first example of

“international style” in America, marked the beginning of the modernist architectural movement.

A few years before his retirement in 1952, Gropius founded the Harvard alumni community, The Architects Collaborative, which was one of the most renowned architecture firms in the world. In 1969, shortly after receiving the title of Honorary Academician, Walter Gropius died at the age of 86. By this time, the ideas of the great German modernist and his theoretical works had become a solid foundation for the architecture of modernism throughout the world.