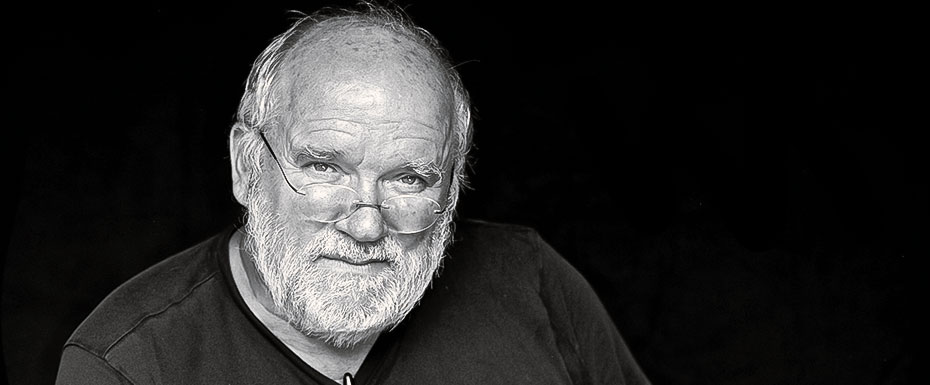

Peter Lindbergh started photography by accident and became one of the greatest fashion photographers of our time. For more than 30 years, Peter had been shooting for the largest glossy magazines. Thanks to him, the world learned about Kate Moss, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, and other legendary supermodels. He revolutionized the world of the fashion industry by defending a woman’s right to be herself through the lens of his camera.

Childhood

Peter Brodbeck was born on November 23, 1944, in the Polish city of Leszno. After 2 months, his family left the country: parents, baby Peter, his brother, and sister drove 2,500 km on a two-wheeled cart pulled by a horse. They stopped in Duisburg, a partially destroyed industrial center of West Germany, located on the banks of the Rhine. Peter’s childhood was spent among shabby factory buildings under a gray, smoky sky. And although the photographer called his homeland ugly, later he was often inspired by its landscapes.

At the age of 14, Peter dropped out of school and took up window dressing in Karstadt. The decorators delighted him: they seemed to him the most beautiful people in the city. They stood in the windows, decorating them with dishes, clothes, flowers, and passers-by stopped, staring at them.

When the time came for military service, Peter avoided it for 9 months in Switzerland but then returned to Germany and entered the Academy of Fine Arts. He soon became disillusioned with his studies: he wanted to do real avant-garde art, but instead, he was forced to paint landscapes until perfection. During this period, Peter was inspired by Van Gogh, his original vision, fierce, and furious creativity. Outraged at the prospect of painting landscapes all his life, he left his studies and hitchhiked to Arles to understand how Van Gogh made himself as an artist.

Peter ran out of money very quickly and was given lodging and food in exchange for work. It was a kind of creative pilgrimage, an attempt to get inspired by the same thing that inspired Vincent, but Peter failed. In addition, he discovered that the winds in Arles are such that it is almost impossible to paint in the street because the wind was scattering the paper. After 8 months, he hitchhiked to Spain.

First Photos

After 2 years of wandering, observing, and thinking, Peter returned to Germany and once again tried to figure out what to do. It was then that he discovered photography. His brother had children, and he asked Peter to film them. Peter was delighted with the spontaneity and honesty of the children in front of the lens. Later, Peter realized that adults could no longer be so natural because they evaluate themselves from the outside. This experience formed the basis of his special attitude to the portrait.

It was almost a miracle that he began to take up photography professionally: he learned that in Dusseldorf, an advertising photographer Hans Lux needed an assistant. Peter happily accepted the job. Taking photographs proved to be much easier for him than trying to keep up with evolving conceptual art.

Recognition

The first glossy magazines that noticed Peter’s talent back in the early 80s were Marie Clare and Vogue US. However, Lindbergh managed to make a resounding revolution in fashion photography only in 1990. The editors of American Vogue repeatedly offered Peter Lindbergh to shoot for them, but he refused every time. Alexander Lieberman, creative director of Condé Nast, drew attention to this and invited Peter to his office.

When Lindbergh arrived, Lieberman asked the photographer why he didn’t want to shoot for American Vogue. “My editors say you don’t want to work with us. Are you crazy? Do you have any idea what you are giving up?” Lindbergh honestly replied that he was not interested in shooting the image of a woman that then flashed on the pages of all major gloss: a chic, rich lady with bright makeup and a crocodile bag. Then Lieberman invited him to photograph the way he wanted and where he wanted, but his first experiments were not appreciated.

Six months later, Anna Wintour took over as editor-in-chief of American Vogue. Sorting out the contents of the drawers in her office, she found those very pictures of laughing girls in white shirts and immediately called Peter Lindbergh. “This is the epitome of a modern woman,” Wintour said. She gave Peter 20 pages and the freedom to decide whom, how, and where to shoot.

The cover of the next, November 1988 Vogue, shocked even the editorial staff of the magazine. Peter photographed an Israeli model Michaela Bercu wearing an haute couture pullover and plain blue jeans. The picture looked atypical for that time – no glamour, a smile, almost closed eyes, disheveled hair. Anna Wintour later said that she looked at this picture and felt the “wind of change”.

Supermodels

A year later, the editor-in-chief of British Vogue, Liz Tilberis, asked Lindbergh to shoot for the cover of the January issue. Peter acted in accordance with his convictions: in the photograph, his favorite models looked into the camera boldly and directly. Minimalistic tops and jeans, natural hairstyles, no retouching, and bright makeup – nothing that could distract from the girls themselves.

The cover girls instantly became stars: after the magazine’s release, George Michael invited them to appear in the Freedom! ’90 music video, they frequented social events and fashion shows. This picture marked the beginning of the era of “supermodels” – for the first time, the models were not just soulless mannequins – they were strong personalities with their own views and beliefs.

Portraits

Peter Lindbergh regularly worked for major glossy magazines, filming advertisements for haute couture clothing. Magazine editors gave him absolute freedom: he himself chose the style, location, and, most importantly, models. Lindbergh looked for intelligence, personality, courage, and a sense of humor. He had an interest in such women in his youth.

In addition to models, Peter enjoyed working with famous actresses. Such filming had its own peculiarities: even though the actresses were used to the camera, looking into the lens and being themselves at the same time remained a difficult task for them.

The pursuit of naturalness in photography permeated all of Peter Lindbergh’s work. Before each shoot, he sat down and wrote down how and what he planned to shoot, but he did it only in order to “sleep at night.” As a rule, everything did not go according to plan at all, and the most difficult thing was letting go of the original idea.

Lindbergh’s Philosophy

When young Peter wandered the Spanish streets penniless, he drew inspiration from the real world. Lindbergh complained about modern photographers who sit in their offices flipping glossy magazines and deciding to do something similar. Lindbergh considered such work blind imitation. Creativity, according to Peter’s beliefs, should always come from the person themselves.

Another important component of Lindbergh’s philosophy was the concept of “self-identity” – honesty to others and oneself. Peter spent over 25 years in meditation to accept himself and the world around him. It was owing to these practices that the people in his photos were so natural: he allowed them to be themselves.