1920-1950s: The First Drawings on the Streets

1920-1950s: The First Drawings on the Streets

The first manifestations of graffiti are considered to be the drawings and writings left on the walls of buildings and freight trains by members of New York City street gangs in the 1920s and 1930s. That’s how gang members “marked their territory” and communicated with each other. Then young people adopted this practice, but initially, they created reactions to socio-political problems, evoking slogans and taglines rather than drawings as a way of self-expression.

1960-1970: Developing a Culture of Drawings on Buildings and Trains

The development of graffiti began on the East Coast of the United States in the 1960s. At that time, the first enthusiasts started to leave their names in random places around the city. Cool Earl and Topcat 126 were among the first writers, but Cornbread – a street artist from Philadelphia, is considered the unofficial founder of this movement. He was one of the first to leave notes signed with his nickname without any political implications.

The starting point in the history of graffiti art is considered the publication in The New York Times in the early 70s. The article told about a young street artist from New York with the nickname – Taki 183, who worked as a courier and spent a lot of time on the subway. There he left marks with his name on each station he passed. Over time, his marks became so numerous that not only passersby but also local journalists paid attention to them. Thus, the artist became the first substitute in the history of graffiti; he is considered one of its founders. Although Taki 183 was not the first artist to leave marks on the streets, the previously little-known graffiti culture got the attention of city residents and the press due to his ubiquity.

The first practice of Taki 183 and other graffiti pioneers was tagging – writing nickname inscriptions left on walls, fences, wagons, and other visible places. Artists gained additional respect for tagging in hard-to-reach locations: for example, at high altitudes or in protected areas. The priority was not on the visual side, and popularity was measured in the number of tags throughout the city. Other notable artists who tagged streets and subways were Hondo 1, Japan 1, Moses 147, Snake 131, Lee 163d, Star 3, Pro-Soul, Tracy 168, Lil Hawk, Barbara 62, Eva 62, Cay 161, and Junior 161.

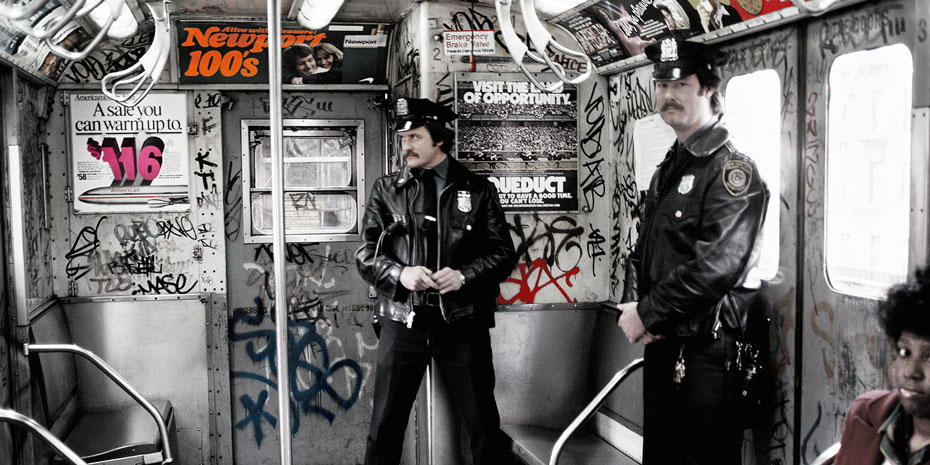

The Subway as a Way of Communication

Through drawings left on the walls of subway trains, artists from different neighborhoods became aware of each other’s existence, so over time, inscriptions almost completely covered both the exterior and interior of the trains. Thus the New York City subway became a means of communication for underground artists.

Back then, the subway was poorly guarded, and trains were rarely cleaned, so the painted subways roamed the city for months, and artists painted the wagons to expose their art to as many people as possible. Therefore the phenomenon known as “bombing” appeared. In order to put tags and drawings on the wagons quickly, artists purposely chose short nicknames like Tee, Iz, Pi, In, which made it much less time-consuming to draw the tags. However, there were also the so-called style writers, for whom style of tags came priority.

Technique Development

One of the first artists who actively practiced the style in the subway was Futura 2000. From the very first works, he saw the potential in drawing in the subway – the very place where passersby saw his first tags and drawings.

The culture became increasingly popular, and artists had to figure out how to stand out among the expanding number of tags. So the most creative artists began implementing graphic details in signatures – strokes, circles, stars, and other similar elements, trying out different artistic styles or playing with the inscriptions’ thickness, type, and color. New practices were quickly picked up by newcomers – so the evolution of styles began and never ended.

Philadelphia artist Topcat 126 came up with the Broadway style and was soon replaced by the Blockbuster style, characterized by huge slanted letters. And another enthusiast under the pseudonym PHASE2 began to use volumetric fonts in the form of bubbles called Bubble Letters.

Blockbuster and Bubble Letters pushed artists to be creative, and the variety of techniques coalesced into one mixed style called Wildstyle. The period from 1975 to 1980 is considered one of the most favorable for the development of graffiti due to the heyday of confrontation between styles of artists who were trying to become more noticeable than others.

Famous artists of this period are Case 2, Seen, Mare, Comet, Repel, Cos 207, Duro, Kade 198, etc.

1980-1990: The Fight Against Vandalism

Only in the early eighties the city authorities began a massive campaign against street drawings, many works were mercilessly destroyed – the lifespan of new works significantly decreased, and the number of guards in the subway and police on the streets noticeably expanded. The city authorities even enacted a series of laws prohibiting the sale of spray paint to minors, and spray cans of paint were kept in safes or secure lockers, just like weapons.

Many artists were uncomfortable with the threat of criminal liability, so some of them have stopped painting on the streets and in the subway, while others began to work legally in studios.

The range of locations available for painting decreased for the remaining artists, and their confrontation in some places began to resemble a street gang feud. Single artists did not dare to go on creative raids unarmed; otherwise, they could have been attacked, while close-knit groups tended to paint in groups for the same safety reasons. Among the veterans who took part in the confrontation were Skeme, Dez, Trap, Delta, Sharp, Seen, Shy 147, Boe, West, Spade 127, Sak, Vulcan, Bg 183, Kenn, Cem, Flight, Airborn, Rize, and others.

Besides, with the beginning of the “war” for the cleanliness of the subway, artists turned their attention to other movable objects – cars. Generally, street artists preferred to paint on vans or small trucks of the city delivery services – these vehicles were running around the city every day, and street artists had one more opportunity to advertise themselves and their artworks.

Graffiti in the XXI Century

Nowadays, street culture is still a controversial phenomenon. Some graffiti drawings are accepted by citizens, but taking into account the constant incidents of vandalism, not everyone has a positive attitude toward the works of street artists. Many newcomers appeared on the street art scene, and the established icons continue to draw on the streets of cities even though they have turned into regular participants of exhibitions and art projects.

Nowadays, street culture is still a controversial phenomenon. Some graffiti drawings are accepted by citizens, but taking into account the constant incidents of vandalism, not everyone has a positive attitude toward the works of street artists. Many newcomers appeared on the street art scene, and the established icons continue to draw on the streets of cities even though they have turned into regular participants of exhibitions and art projects.

A characteristic feature of modern graffiti culture is commercialism. When big companies realized the popularity of street drawings, artists became more and more often involved in realizing advertising campaigns. As a result, the manifestations of graffiti in mass culture can be found everywhere – from ads and fashion to films and video games.