The American poetic avant-garde of the first half of the twentieth century avoided overly conspicuous experiments with language; on this point, it was different from Russian Futurism or French Dadaism. The exceptions were only two authors – Gertrude Stein, until then on the periphery of literary life, and Cummings, immersed in its center.

E. E. Cummings – that is how he preferred to write his name, created a considerable number of poems and other texts, each of which solves a certain formal problem. He strove to give the English language uncharacteristic flexibility – breaking all the school grammar rules to make the poetic content more expressive. There were two poles in American interwar poetry, Cummings and Robert Frost – they are often referred to in pairs as the most widely read American poets. The first one rejected poetic tradition and boldly transformed language, and the second clung to old forms, proving by his own example that they could express universal, never-aging meanings.

Biography

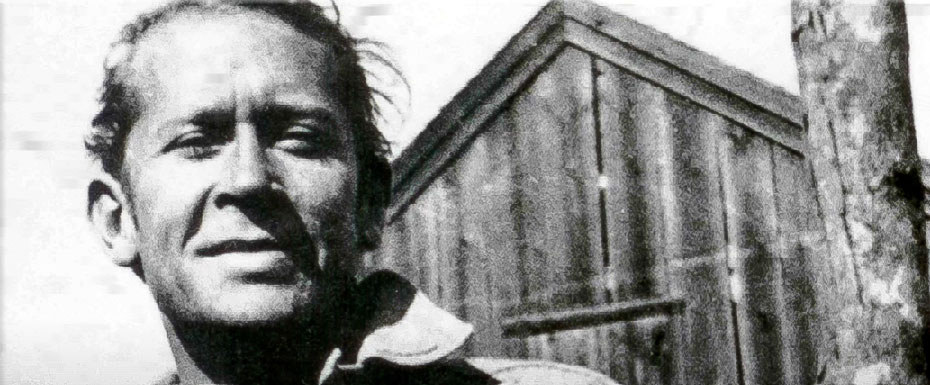

Edward Estlin Cummings was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in a liberal Unitarian church family. His father was a professor at Harvard University and later gained all-American fame in the Southern Congregational Church in Boston.

Cummings wrote poetry from an early age and always dreamed of being a poet, and his family encouraged this passion. He graduated with honors from Harvard and was active in university literary life as editor and contributor to “The Harvard Monthly.”

In 1917, during World War I, Cummings enlisted with his university friend, later the famous writer, John Dos Passos, as a volunteer in the American Medical Corps. They were waiting to be sent to the front in Paris, which was then the poet’s favorite city – he would return to it often in later years. The military censors, who examined the letters of Passos and Cummings to their relatives, suspected them of spying, and as a result, they spent four months in prison during the investigation of this case. It was an experience that formed the basis of “The Enormous Novel” (1922), written a few years later.

After the liberation, Cummings spent several more months in the army, this time in the United States. In 1926, his father died in a car accident, and his mother was seriously injured. This tragic event is what Cummings’ biographers associate with his “conservative twist”: he gradually moved away from the leftist and democratic sympathies of his youth and began to embrace republicanism, so that in the 1950s, he supported Senator McCarthy’s anti-communist campaign. Cummings traveled extensively, frequently visiting Paris, North Africa, Mexico, and even the Soviet Union at the dawn of the Stalinist era in 1931.

Context

Cummings has always been at the center of intellectual and creative life: when he was young, his parents’ house was frequently visited by the famous psychologist William James, whose name is often associated with the invention of stream of consciousness, one of the leading modernist writing techniques used by James Joyce and Gertrude Stein. A close friend of the poet was John Dos Passos, a writer whose montage-like, documentary-like writing has had an enormous influence on world literature, far beyond America’s borders.

Poetics

If Russian futurism, in its experiments with language, sought the basis for a new utopia capable of transcending cultural and state borders, for Cummings, this challenge was irrelevant. From his perspective, it was not a matter of inventing a new reality but finding appropriate means for reflecting the existing reality — this kinship with other American modernists, above all with William Carlos Williams. But while the latter believed that everyday language was sufficient to capture reality, Cummings believed that existing language could not be sufficient: only by inventing a new language can one fully cognize the world. This language remains strictly individual, almost diary-like: often the choice of this or that word is conditioned by personal associations which are not transparent to the external reader and cannot be deciphered, each word assumes several meanings (the reader encounters all this in the works of Gertrude Stein, too). That’s why Cummings’ poems are highly ironic: innocent landscape lyrics can turn into erotic scenes through obscene allusions and heroics into overt satire.

Influence

Cummings was one of the inventors of the irony type that became widespread in twentieth-century art, and, one might say, he became the hallmark of that art. Edward Estlin Cummings can be called paralogical: with this type of irony, the message means sharply opposite things – heroism turns into meanness, truth into a lie, good into evil, and so forth.

The avant-garde culture of the 1960s entirely borrowed this peculiarity of Cummings’ writing: for example, traces of it can be seen in the novels of Thomas Pynchon or the art of Andy Warhol. Cummings was long unknown to a global audience, and even now, his popularity lags far behind that of other American poets such as Wallace Stevens and Robert Frost. Nevertheless, Cummings is an important figure in American literature, and we encourage every poetry lover to read his beautiful works!